Israel crisis a battle for country’s identity

While flames lapped around melting tyres on Tel Aviv’s main highway, doctors walked out of hospitals and Israel’s main airport was shut down, Benjamin Netanyahu kept a country waiting.

Unprecedented protests and strikes gripped Israel on Monday, the climax of months of dissent over the government’s plans to strip power from Israel’s judges.

Now with a nation in crisis, all sides watched for the prime minister to act.

When he finally appeared on national TV – maximising the impact with a live address at the top of the 20:00 nightly news shows – he began by likening his position to a story about King Solomon.

Just as the biblical monarch had to judge which of two competing women was the real loving mother of a baby, he had made his own decision when it came to the two sides contesting his reforms.

He announced he was pausing the judicial changes until the next session of parliament, and would “extend my hand” in “compromise” and “dialogue” with parliamentary opponents.

The announcement appears to have done enough to bring the crisis back from the brink for now, and to give the official opposition space to say they will hold him to his word of negotiated compromise.

It has also split the vast movement that was campaigning against the reforms – with the bigger opposition parties in parliament giving his decision a cautious welcome, while leaders of the street demonstrations denounced it as a temporary freeze to “gaslight” critics. They vowed to push on with protests.

But the much bigger issues underlying this crisis – Jewish Israelis bitterly split over the role of religion and state, the dangerous fragility of checks on government power, and a total void of any political horizons for a shared future with the Palestinians – remain totally unresolved, and are only getting more aggravated.

Mr Netanyahu went on with his metaphor – just as one mother was unwilling to see King Solomon cut the baby in two, he was unwilling, he said, to divide the country.

Many of his critics say, however, that he actually had months to dilute or stop the contested reforms he started. They accuse him of letting the country get to boiling point first.

For him, his words carried a clear implication – a minority among his opponents were to blame for the crisis; they were prepared to cut the baby in half. He said he was there to act responsibly. “I am unwilling to cut the nation in two,” he said.

It felt designed to draw most attention to the dividing lines, while giving Mr Netanyahu the air of being the only one who could save the country from itself.

Deep divisions

The protests had intensified after Mr Netanyahu returned to power at the end of last year, leading the most right-wing, nationalist government in Israel’s history and promising to curb the powers of the judiciary. He had engineered an alliance of far-right parties to get the coalition numbers for his return to power, and has become increasingly reliant on them in this crisis.

The judicial changes would have given the government full control over the committee which appoints judges and would ultimately strip the Supreme Court of crucial powers to strike down legislation it saw as effectively unconstitutional.

They sparked one of the greatest political and social disputes of Israel’s modern era – much of which hinged on opponents’ fears that his government of the ultra-religious and far right was speeding the country towards theocratic rule.

Others pointed out the changes could ultimately help shield Mr Netanyahu from his corruption trial – an accusation he rejected.

Supporters of the plans said they would stop “over-reach” by judges they have repeatedly accused of acting politically against the interests of their nationalist agenda, which they say is backed a majority of Israelis.

But opposition spread deep into the ranks of military reservists, causing security chiefs to reportedly warn Mr Netanyahu the dissent was affecting the operational capacity of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

This led the Defence Minister, Yoav Gallant, to publicly urge a halt to the reforms. Mr Netanyahu then fired him, sparking Monday’s crisis.

Ceasefire

Much of the delay to Mr Netanyahu speaking on Monday happened because he was negotiating with far-right ministers in his coalition, establishing their price for agreeing to pause the reforms.

That became clear on Monday evening, when the far-right National Security Minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir of the Otzma Yehudit (Jewish Power) party, said he would now press ahead with his plans for a “national guard”, apparently funded by part of a multi-billion dollar budget.

This would be a deployable armed force answerable directly to him, which he has previously spoken of as meant to quell trouble in “mixed” Jewish-Arab cities, or in areas of high crime among Palestinian citizens of Israel.

His opponents – and even parts of the Israeli police – see it as a private militia. Berti Ohion, a former head of police operations, said on Tuesday that such a force would create “chaos”, with two security bodies operating in the same area.

Mr Ben-Gvir’s political background is among followers of a violent Jewish supremacist movement which is outlawed in the Israeli parliament. He has previous convictions for racist, anti-Palestinian incitement and supporting a terrorist group.

His own supporters rallied outside the Israeli parliament on Monday night, while far-right groups were later filmed attacking Palestinian passers-by.

Meanwhile, Palestinians in the occupied West Bank believe Israeli settlers feel more emboldened than ever by the presence of their ultra-nationalist parties in Israel’s government – an atmosphere helping fuel the recent surge in settler attacks.

As Monday’s political crisis intensified in Jerusalem, six Palestinians were injured in an attack on homes and vehicles in the West Bank town of Hawara.

Last week, two Israeli soldiers had been wounded in a Palestinian drive-by shooting attack there.

The town was the scene of an hours-long rampage by armed settlers last month, leaving one man dead and hundreds injured, after two Israelis were shot dead there by a Palestinian gunman.

Israel’s far right finance minister Bezalel Smotrich later called for the town to be “wiped out”. Residents told the BBC at the time that Israel’s security forces stood by, some firing stun grenades and tear gas at victims of the attack while protecting the settlers.

Some Israeli anti-government protesters contrasted the police’s use of force against them with their lack of action against the settlers in the West Bank. “Where were you in Hawara?” they chanted at their security forces in Tel Aviv.

The demonstrations have seen a role for the Israeli left wing and the remnants of the “peace camp” – but it has not been highly prominent. In fact, early in the protests some demonstrators attacked others holding Palestinian flags.

Instead, the major opposition groups have claimed this outpouring of mostly liberal, secular Israelis as the true demonstration of Zionism, patriotism and democracy.

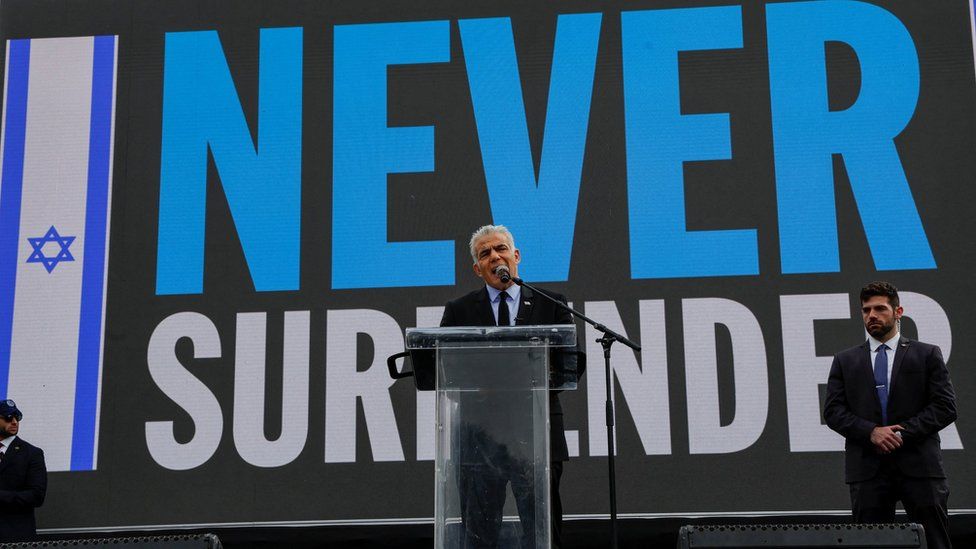

The demonstrations were filled with Israeli flags. Opposition leader Yair Lapid began referring to Mr Netanyahu’s religious and far right coalition as “anti-Zionist” and a dangerous threat to national security.

This is a battle for the identity of the state.

With no detailed timeframe on Mr Netanyahu’s pledge to park the reforms or for the apparent negotiations, his speech on Monday marks only a ceasefire; the fighting is set to resume.