France riots: Can Paris prevent tensions igniting again?

Calm has returned to La Grande Borne. Local mafia again exercise lazy control from the doorways of this vast housing estate south of Paris; their guns on show, their faces hidden.

After days of riots, there is no sign of the police.

“In some banlieues (suburban estates), they are better equipped than us; they have better weapons,” one police officer told us, on condition we keep his identity hidden.

The officer we spoke to spent last week facing rioters in several estates around Paris, as towns and cities across France erupted in rage at the killing of Nahel M, who was 17.

He was shot dead at a police traffic stop in Nanterre, west of Paris, and the policeman who fired through the car window is in detention accused of “voluntary homicide”.

The riots were “super-violent”, the officer said. But the problem between French suburbs and French police goes much deeper than occasional eruptions of fireworks and Molotov cocktails.

Distrust and resentment smoulder beneath the surface in places like La Grande Borne, less visible than the weapons carried by gangs here, but just as likely to explode.

“When we intervene in an estate, there is fear on both sides,” the officer said. “But the police should not be afraid. Fear doesn’t help in making the right choices.”

The question now being asked, from the estates to the Élysée Palace, is how to prevent these tensions igniting again.

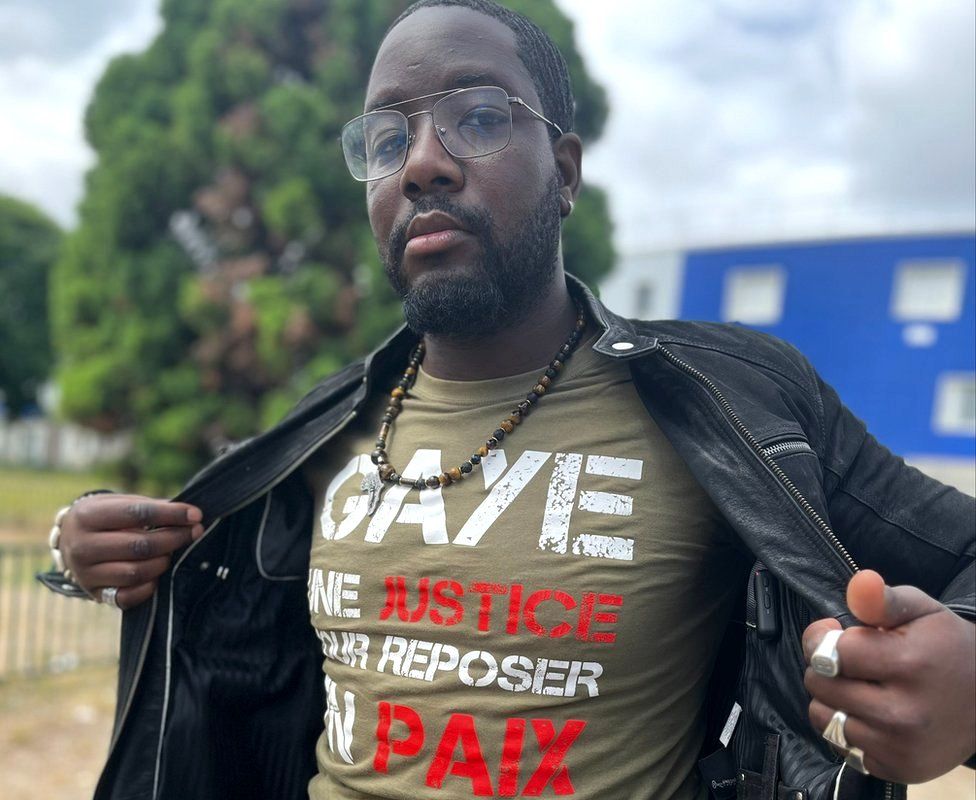

Djigui Diarra is a film-maker who grew up in La Grande Borne, which is one of the poorest housing estates in France.

“My first encounter with police was when I was 10 years old,” he explained, as we sat in the simple concrete playground he used to visit as a child, surrounded by low-rise apartment blocks.

It was a police identification check on an older member of his group, someone he saw as a “big brother”.

“They were really rude, so my big brother responded and they put him down [on the ground],” the 27-year-old said. “This was my first encounter with police and as a kid I said to myself, ‘this will be my natural enemy'”.

That was around the time that France scrapped community policing, known in the country as the “police of proximity” – something Djigui believes was a big mistake.

“With the police of proximity, there was a lack of violence, a lack of criminality,” he said. “The language [was] great; they respected people. You have to put people together to feel each other.”

Now they only come when there’s trouble, he added.

Djigui – whose name means “hope” in Mali’s Bambara language – said he had been called “gorilla” and “monkey” by police officers during ID checks.

Four years ago, he made a film called Malgré Eux (In Spite of Them) which explored the racial divisions between residents and police in his community.

It’s something other community leaders, in other banlieues, bring up too.

In Gennevilliers, on the other side of Paris, Hassan Ben M’Barak leads a network of local associations that was created during weeks of rioting back in 2005.

“We need at least 20% or 25% of the police who patrol the neighbourhood to come from minority ethnic backgrounds [or] to come from the neighbourhood,” he said. “That’s a really important aspect.”

Since 2005, he explained, the situation has got harder to control – not only because of changes in policing, but changes in funding policy too, with money directed towards urban regeneration and away from local associations on the ground.

What’s striking this time, he said, was that “no one – no association – has called for calm” because they no longer have the authority to influence the situation.

This week, French media reported that the police officer charged with Nahel’s homicide told investigators that he pulled the trigger because he was afraid the 17-year-old would drive off and “drag” his police colleague with him.

The traffic policeman, named as Florian M, also denied threatening to shoot the teenager in the head.

The shooting, and the riots that followed, dominated French media for days. But many believe media coverage here is just as important as policing and policy in fuelling divisions between the banlieues and the rest of France.

“They have to talk about great histories [stories] in the suburbs, not only when there are riots,” Djigui said. “That will reduce the racism and fear in others.

“And we in the suburbs have to consider every little brother, every little sister, as ours. We have to consider every member of this [estate] as our family.”

Djigui is now working on a new series about policing in France’s suburbs, and said he believes that those beyond the banlieues are starting to wake up to his message.

“When the yellow vest strikes happened, they understood why we in the suburbs were, like, police brutality is abominable. I said to them, ‘better late [than never]’.”

The yellow vest protests, which broke out across France in 2017, sparked a national debate about police brutality after a number of protesters were seriously injured by police.

For now, though, the fires have subsided in the banlieues and so has the attention they brought. And the towering apartment blocks that ring France’s prosperous cities are sinking out of sight again.