Ukraine war: West’s modern weapons halt Russia’s advance in Donbas

Soldiers on the front lines in eastern Ukraine say sophisticated Western weaponry has stalled Russia’s furious bombardment. But is this merely a brief lull, or a sign that the tide is turning in the conflict?

Five plumes of smoke pierced a clear blue sky on a hillside just north of Bakhmut, an almost deserted farming town that has been under sustained Russian bombardment for weeks.

“This is no life for us. Nowhere is safe. I honestly wish my life was over,” said 86-year-old Anna Ivanova, bending low, with the help of a walking stick, to pull weeds from her garden, as two Ukrainian jets roared low overhead.

Ten minutes later, a succession of five or more loud booms rolled over the brilliant yellow sunflower fields to the west.

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERS

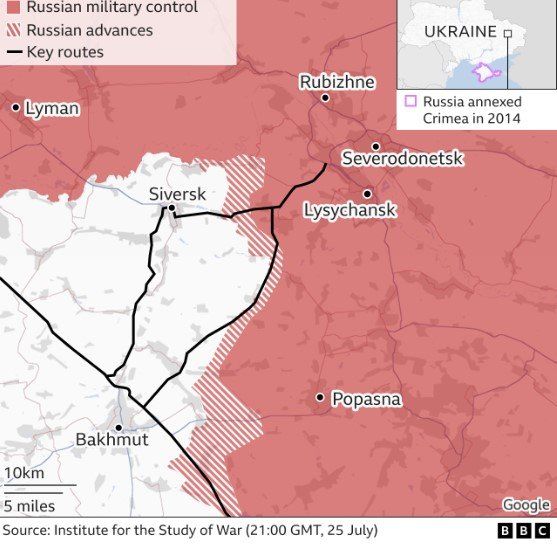

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERSFor anyone driving close to the meandering front lines of Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region – from the shattered city of Slovyansk in the north, to the abandoned farming villages near Donetsk in the south – it can feel as if Russia’s grinding, seemingly indiscriminate bombardments remain as frenzied as ever.

But in the corner of a wheat field outside Donetsk, the commander of a Ukrainian artillery unit who asked to be known only by his first name, Dmitro, was adamant. “They’re not firing as often. The rate of artillery fire [from Russian forces] has dropped by half. Maybe even more, maybe by two-thirds,” he said, patting the side of a large green vehicle beside him.

The vehicle – a self-propelled artillery piece with a huge barrel pointing south towards Russian-held territory – is a French manufactured Caesar, one of the growing number of sophisticated Western weapons that can now be spotted moving along country lanes throughout Donbas. Dmitro, and many others here, believe they are helping to turn the tide against Russia.

With a deafening blast, the Caesar fired the first of three shells at what Dmitro said was a Russian infantry unit and several artillery pieces 27km (16 miles) away.

“We’re much more accurate now. And we can hit them much further away,” he said, with a grin. Within a minute, the artillery team had fired two more shells, and the vehicle was already moving away, fast, before Russian artillery had a chance to track its position and return fire.

In recent weeks Ukrainian civilians and soldiers have watched, often gleefully, as drone footage and other videos uploaded on to the internet appear to have shown a series of massive explosions in Russian-held territory.

It is widely reported that these are large ammunition stores, kept far behind the frontlines, but now within reach of the newly arrived Western weaponry, including American Himars and Polish Krab howitzers.

“Listen to that silence,” said Yuri Bereza, a bearded 52-year-old commanding a volunteer unit tasked with defending Slovyansk. For well over an hour one recent morning, on a visit to a network of defensive trenches east of the city, not a single explosion could be heard.

“That’s all because of the artillery you’ve given us – because of its accuracy,” said Bereza. “Before, Russia had 50 gun barrels for every one we had. Now it’s more like five to one. Their advantage is now insignificant. You could call it parity.”

But Bereza, like Dmitro, emphasised that Ukraine needed far more Western weaponry in order to launch an effective counter-offensive.

“They can’t beat us, and we can’t beat them here. We need more equipment, especially armour, tanks, aviation. Without these things there will be enormous loss of life. That’s the way Russia is used to waging war. They throw lives away,” said Bereza.

“Ideally, we’d like three times as many [Western weapons] as they’ve already sent us. And quickly,” confirmed Dmitro.

But a lack of weaponry is not the only thing potentially thwarting Ukraine’s determination to liberate captured territory. Despite the reduced Russian bombardment, the Kremlin’s forces continue to push closer to the strategic town of Bakhmut, raising concerns among Ukrainian forces about a lack of manpower and training.

“Here’s a simple trick,” shouted a burly figure, lying on a dirt track and aiming his rifle, surrounded by forty attentive Ukrainian soldiers.

“Bring your leg up like this,” said the man, a former British paratrooper, who was part of a private group offering support to a Ukrainian brigade that had recently arrived to reinforce the frontlines.

The Ukrainians were all volunteers, and had only had a couple of months basic training. Their commanders had reached an informal agreement with the Western trainers, for a five-day course.

“Of course, it’s scary. I’ve not seen war before,” said the unit’s 22-year-old commander, a lawyer, who asked that we not use his name.

“Worrying is the fact that these guys… lack the basic soldiering skills that the West is used to,” said another trainer, Rob, a former US marine.

For now, Western governments have refused to send officials, or contractors, into Ukraine to help with military recruitment and training efforts. A handful of private organisations are operating here, independently.

“It’s a drop in the ocean. But it makes a difference, on a small scale,” said Andy Milburn, a retired US Marine colonel, as he watched a training session.

He stressed that his Mozart group had “zero” contact with, or support from, the US government, but he criticised Western nations for a “squeamish” and “short-sighted” refusal to engage more directly.

“It’s ridiculous. But these guys have lost so many people that they just don’t have [enough Ukrainian instructors],” he said. “The West needs to plan for that now.”