‘I was chased by skinheads when I arrived in Leicester’

“They pulled out the stakes from the ground and then started to hit the people and families with young children.

“It was just horrible and my brother just grabbed my hand and we ran and ran like mad.

“It was very scary and I was concerned about the people who might have got hurt.”

Nisha Popat recalls, 50 years later, how she was chased by skinheads, after arriving in the UK, aged nine.

Fleeing persecution in their home, in Jinja – after President Gen Idi Amin gave Asians 90 days to leave Uganda – she had travelled to Leicester with her younger brother and three older sisters.

Her parents joined them four weeks later.

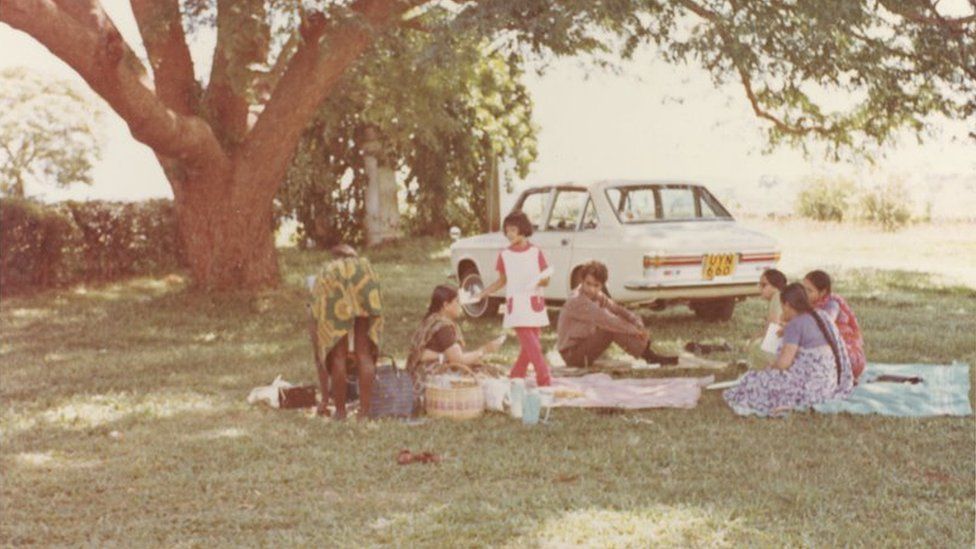

But swapping the serenity of life in Uganda, where climbing mango trees was the norm, for “strange, cold Leicester” took some getting used to.

“It was really strange. Their houses seemed different. Everything seemed different. It was October, so it was getting cold,” Ms Popat says.

“Part of me felt it was like an adventure and I think I didn’t totally grasp that this would be home. My mum kind of made it out to be, ‘You’re going on holiday – you’re going to have a good time.'”

IMAGE SOURCE,NISHA POPAT

IMAGE SOURCE,NISHA POPATMost of those who fled Uganda had British passports and settled in the UK.

And Ms Popat’s family was one of thousands to settle in Leicester, despite a council advert in the Uganda Argus discouraging Ugandan Asians from moving to the city.

“I could see I was different. I thought I knew how to speak English – but people looked at you weirdly when you spoke,” she says.

“And then as I got older and started secondary school, that’s when the racism started and the name-calling.”

She describes being racially abused and told she “smelled of curry”.

“It was really hurtful and quite confusing as well because, as a child, you’re not quite sure where this is all coming from,” Ms Popat says.

And the violent scenes she saw, aged 12 – at a funfair in the Belgrave area – have always stuck with her.

IMAGE SOURCE,NISHA POPAT

IMAGE SOURCE,NISHA POPAT“It had started to sink in that I was different and it was OK to be different but that I needed to kind of celebrate that difference,” Ms Popat says.

Leicester already had an established Asian community – but the Ugandan Asian movement transformed it, she says, and it is now a welcoming city.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES“It’s been a really important lesson to have this Ugandan Asian community,” Ms Popat says.

“It’s been a catalyst for so much both in terms of its economic growth, in terms of its social and cultural growth. It’s brought new life into the city.

“This doesn’t mean Leicester is perfect. Like many other cities, you do have people who can still be racist. But I think Leicester has come such a long way since 50 years ago.”

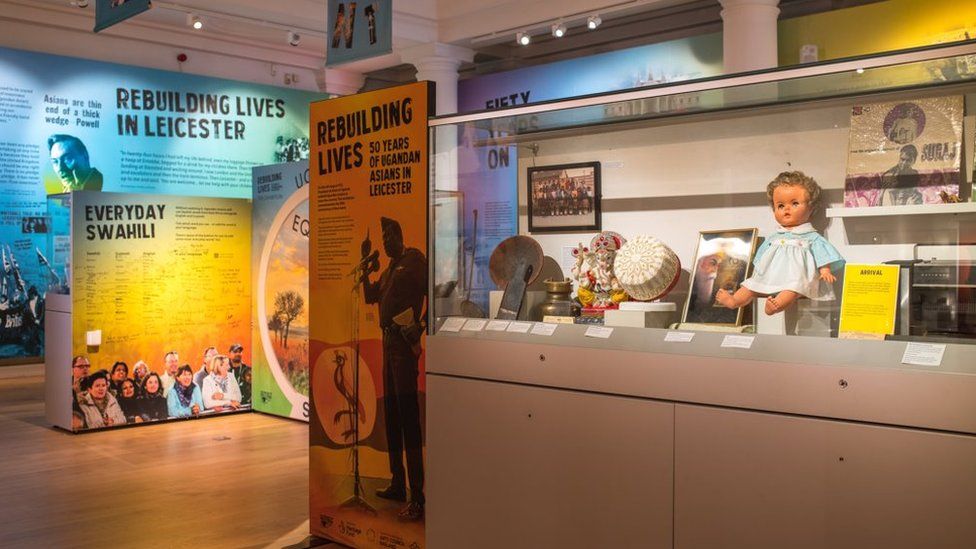

Ms Popat is the project director of an exhibition – Rebuilding Lives: 50 Years of Ugandan Asians in Leicester – that is part of a programme of regional events to commemorate the anniversary.

This summer, she will return to Uganda for the first time, with her daughters.

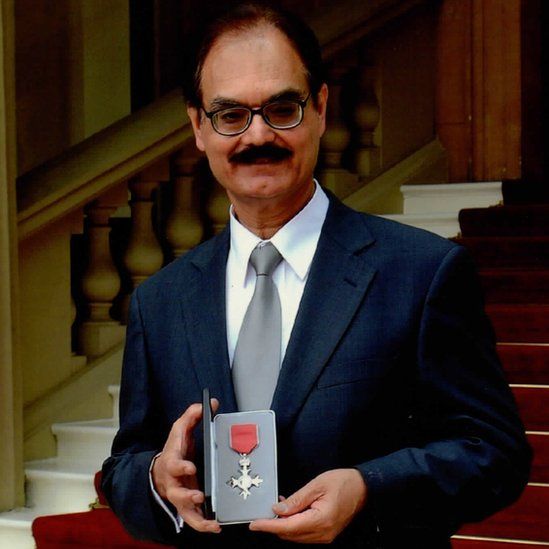

IMAGE SOURCE,MANZOOR MOGHUL

IMAGE SOURCE,MANZOOR MOGHULManzoor Moghal was a prominent member of Uganda’s Asian community before the expulsion, having been involved in politics from a young age, and the movement for Uganda to become independent, and stood for parliament.

Recalling the moments after Amin’s order, he says: “We tried to flee the country in the darkness of the night with my wife and children, because my life was threatened.

“I came to know that I was on his hit list and I would’ve been bumped off.”

With a friend in Leicester, they too headed for the city, not caring about the city council’s advert.

Mayor Sir Peter Soulsby has said he was “angry and saddened” by the council’s actions at the time, while another councillor called the advert “foolish and crude”.

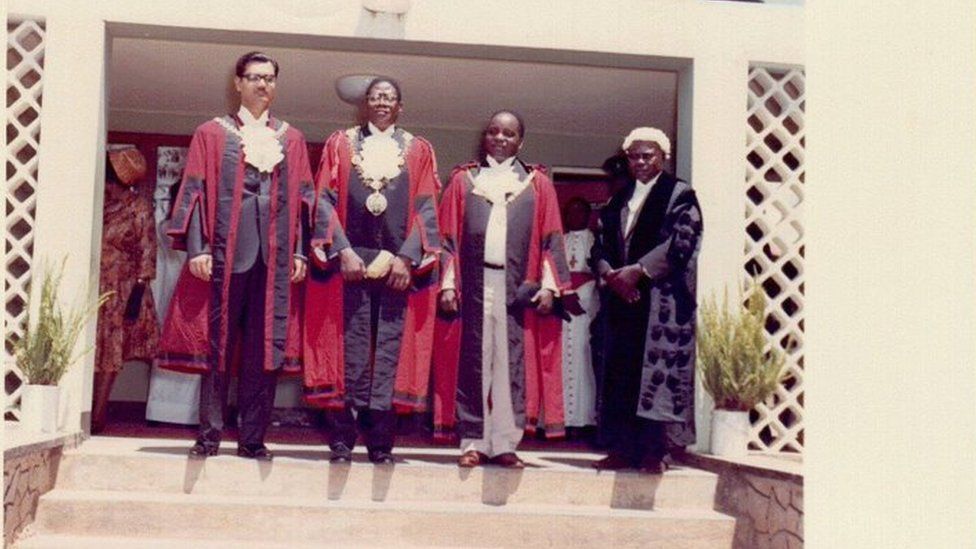

IMAGE SOURCE,MANZOOR MOGHAL

IMAGE SOURCE,MANZOOR MOGHAL“They were unwise, politically misled, in taking that out, that advert,” Mr Moghal, who lives in the Stretton Hall area, says.

“It really backfired on them.

“Because of that advert, many Uganda Asians came to Leicester to see what was so special about Leicester that they were being debarred from coming here.

“So when they came to Leicester they saw the nucleus of an Asian community.

“There were temples, mosques, gurdwaras, Indian fashion shops, Indian community and they liked it because that’s how they wanted to live, not among strangers but amongst people of their own kind – and that’s how people are all over the world.”

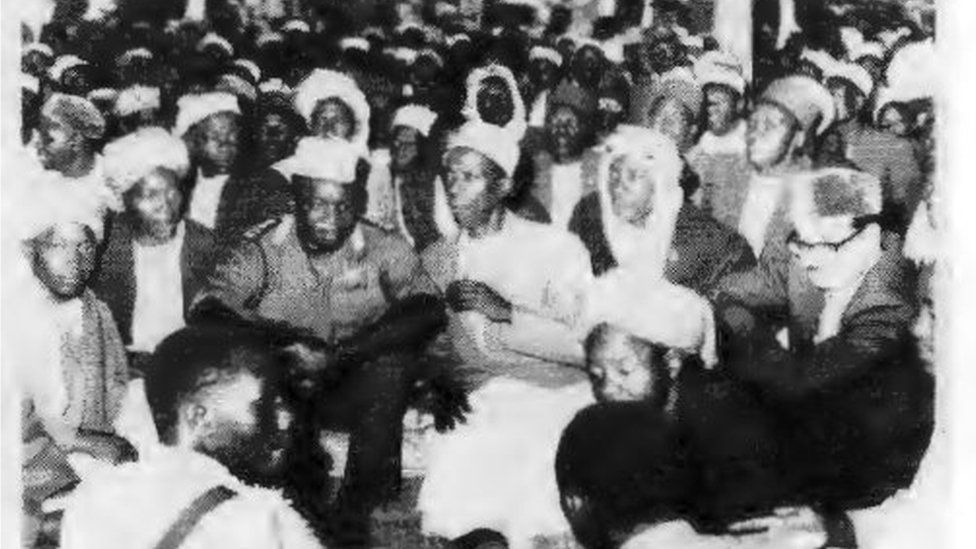

IMAGE SOURCE,MANZOOR MOGHAL

IMAGE SOURCE,MANZOOR MOGHALNevertheless, Ugandan Asians were “mocked” and laughed at on their arrival in the city, Mr Moghul says, giving a sense of being “downgraded by a nation which should have protected them 100%”.

“It did not – it failed to protect Uganda Asians,” he says.

“It was dismissive of Idi Amin’s intentions. It never took him seriously and the British government never provided any positive assistance or assurance to the Ugandan Asians in accepting them.”

IMAGE SOURCE,NISHA POPAT

IMAGE SOURCE,NISHA POPATGurharpal Singh, Professor of Sikh and Punjab studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies University of London, says: “The Ugandan Asians were refugees who transformed the image of refugees.

“We think of Ukrainian refugees coming and settling now – but they came at a time of a great deal of hostility. They took it on, they bore that and transformed their life experience and turned Leicester around into a wonderful, multicultural city.”

Rebuilding Lives: 50 Years of Ugandan Asians in Leicester is at Leicester Museum and Art Gallery until 23 December.