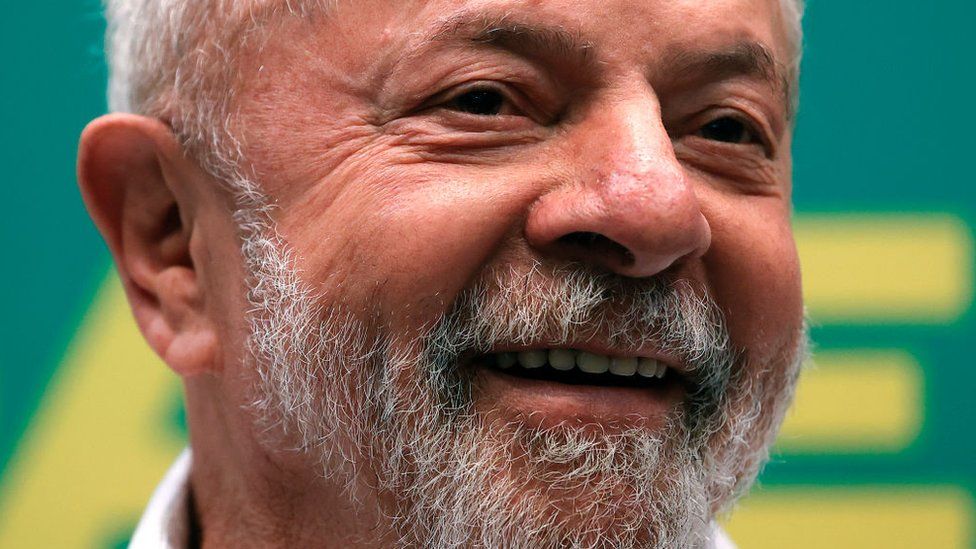

Brazil polarised as Bolsonaro seeks re-election and Lula aims for comeback

Brazilians are heading to the polls on Sunday in an election which could see one of the world’s most populous democracies switch from a far-right to a left-wing leader.

Voting is compulsory for the more than 156 million Brazilians eligible.

Incumbent Jair Bolsonaro is seeking a second term after four years in power but is being challenged by ex-President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

A result is expected within hours after polls close at 17:00 (20:00 GMT).

Poles apart

The campaign has been acrimonious and polarising with the two main candidates trading insults.

During a televised debate on Thursday, President Bolsonaro called Lula, who served time in prison after being convicted on corruption charges, an “ex-inmate” and a “traitor”, while Lula labelled the president “a liar”.

Five key facts about Lula

- 76 years old

- left-wing

- former metal worker

- was president from 2003-2010

- imprisoned in 2018 but conviction was later thrown out

Lula was not able to run in the last election in 2018 because he was in jail and barred from standing for office.

His Workers’ Party colleague, Fernando Haddad, did not have the same name recognition and failed to inspire left-wing voters in the way Lula does.

Amid widespread discontent with mainstream politics and anger at corruption scandals which had tainted the Workers’ Party, far-right lawmaker and former army captain Jair Bolsonaro was swept into office.

Five key facts about Bolsonaro

- 67 years old

- far-right

- former army captain

- running for a second consecutive term

- has cast unsubstantiated doubts on the trustworthiness of Brazil’s electronic voting system

But with Lula’s conviction annulled by the Supreme Court, the former president is very much back on the scene and opinion polls give him a double-digit lead over Mr Bolsonaro.

There are nine other candidates in the running, but polls suggest their support does not amount to more than 10%, leaving Lula and Mr Bolsonaro to battle it out.

One round or two?

Brazil’s electoral system requires that a candidate win more than 50% of the valid votes cast in order to be declared president outright.

If none of the candidates gets the necessary votes in the first round on 2 October, a run-off will be held between the top two on 30 October.

Opinion polls have consistently shown Lula in the lead and there is a small chance he could win the presidency in the first round, something which has not happened since centre-right President Fernando Henrique Cardoso was re-elected in 1998.

However, many Bolsonaro supporters remain confident of victory and the president himself believes he can win outright in the first round.

He has also cast doubts on Brazil’s electronic voting system, arguing – without providing evidence – that it is open to fraud.

He is adamant that in case of losing, it will be because the voting was rigged.

Brazil’s electoral authority has dismissed these allegations as “false and dishonest”, but the attacks have raised concerns that Mr Bolsonaro may not accept an outcome unfavourable to him.

Statements made by the president in the lead-up to the election, such as that only God could remove him from office, have created a tense atmosphere, with some voters wary of speaking out in public.

This was certainly the case with the two sisters I met on a street corner in Rio waving Lula flags, who asked me not to take their photo or give their names.

The younger one said she wanted Lula to win, because she liked how he had opened up Brazil’s education system to the poor and people of colour, like her.

At 46, she has not given up on her dream of becoming a vet. But, as an evangelical Christian, she is also concerned about rumours she has heard that a Lula government could rein in the growing power of evangelical churches. “If he goes against the church, that’s it, he’ll lose my vote,” she says.

Her sister thinks “all politicians are thieves”, but is convinced that for poor people like herself, “Lula is the lesser of two evils”.

She says she voted for Jair Bolsonaro in 2018 as she was “looking for change” after a raft of corruption scandals which tainted Lula’s Workers’ Party.

But with food prices and the cost of living on the rise, she is now looking for change again. She was going to back former governor Ciro Gomes but, with polls showing him trailing far behind in third place, she decided to back Lula.

Poverty on the rise

Growing levels of poverty – hunger is said to affect more than 33 million of Brazil’s 214 million inhabitants – have boosted support for Lula, who during his previous presidencies lifted millions out of poverty through generous social programmes.

But the growth of evangelical churches has played into the hands of President Bolsonaro, who – while himself not evangelical – has, nonetheless, aligned himself closely with evangelical pastors.

One of those supporting the incumbent is Jean Regina, vice-president of the think tank Brazilian Institute of Law and Religion.

According to him, religious leaders find “that the president’s rhetoric aligns with what they hold dear, which is the free exercise of their religion and many moral aspects of social life”.

He praises the president for exempting churches from lockdowns during the Covid pandemic and hopes that, if re-elected, the president will lift a ban on missionaries entering areas set aside for indigenous peoples.

While Mr Regina highlights Mr Bolsonaro’s defence of the traditional family, this is something Vin Vogel, author and illustrator of young readers’ books, objects to.

He says that “as a citizen who happens to be homosexual, I was so depressed when this openly homophobic person” was elected.

But his rejection of President Bolsonaro goes further than that. “There is nothing in this man that I like. He is a threat to democracy, to LGBT people, to indigenous people, so when he was elected, I thought, ‘The bully has won the fight.'”

Similar to other Lula voters, for Mr Vogel, investment in education is the key to levelling inequalities in Brazil.

“There is no way we’re going to thrive as a nation if people can’t get educated and get access to leisure and culture,” he says, adding that he messaged Lula’s campaign on social media with a plea to invest in education.

With tension running high as both Bolsonaro and Lula supporters continue to believe in victory for their candidate, Mr Vogel is one of many voters who has decided to keep a low profile on election day and the days after.

“I won’t wear any badges or stickers to show who I’m voting for,” he says referring to rumours that there could be outbreaks of violence if the hopes of President Bolsonaro’s most ardent supporters were to be thwarted.