Angry suppliers to Missguided weigh up legal action against ‘reckless’ owners

Suppliers to the collapsed fast fashion brand Missguided have filed an official complaint to the Insolvency Service and are considering legal action over what campaigners say was “a reckless approach” by the company’s private equity owners.

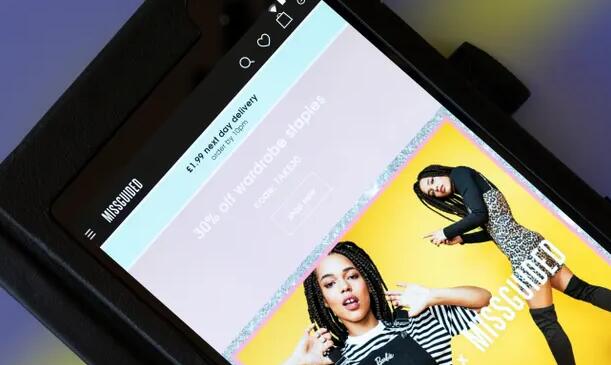

Missguided called in administrators from advisory firm Teneo on Monday after months of seeking new funds after a boom in sales of clothing online during the pandemic went into reverse when shops reopened. Britain’s fast fashion retailers have come under huge pressure from supply chain costs and delivery delays, while battling new entrants such as China’s Shein.

More than a dozen suppliers based in the UK, mostly in Leicester and Manchester, say they are collectively owed millions of pounds for orders, some of which were placed as late as last month with deliveries demanded even on Monday, the day Missguided went into administration.

The company continues to trade while a buyer is sought, but customers are complaining on social media that they have not received deliveries of orders and are still awaiting refunds.

Meanwhile, hundreds of UK factory workers are understood to have lost their jobs as garment makers struggle to find new business.

Campaigners said some Leicester factories are entirely reliant on business from Missguided, which was founded in 2009 by Nitin Passi. He left in April, a few months after private equity group Alteri bought a controlling stake and took seats on the board. Ian Gray, the former chief executive of Tottenham Hotspur football club and chairman of organic veg business Abel & Cole, was appointed executive chair of Missguided last month.

One supplier said he was considering legal action as he believed Missguided could have acted fraudulently if it continued to place orders while “administration was on the horizon”. Two suppliers said they had been told by the firm that it was “business as usual” less than six weeks ago.

Nadeem Arshad, the owner of Manchester-based fashion supplier Moku, said his business was “on the brink of collapse” as it was owed almost £500,000 for recent orders and was “now seeking legal advice and joining forces with other suppliers who find themselves in this catastrophic position”.

Another said his complaint to the Insolvency Service said Missguided had “bought garments from us in the last three months even though knowing the company was in trouble and no thoughts of all the costs behind the making of our products”.

Alex Jay, head of insolvency and asset recovery at law firm Stewarts, said: “Where a company carries on trading when its directors know there is no reasonable prospect of avoiding insolvency, then that can form the grounds for a claim.

“The question will be whether the continued trading has increased the overall deficit owed by the company to its creditors as a whole – in other words, have the directors made the position worse by keeping the company alive for longer than they should in the hope of turning the business around. If they have done that, then claims may well be pursued.”

Another insolvency expert, Brian Burke at advisory firm Quantuma, said there was unlikely to be a “short-term fix” for suppliers owed money and any legal action would take time. He added that they were likely to have to wait for administrators to assess how much unsecured creditors could expect to be paid and added: “Unfortunately for the majority my assumption is they will be looking at significant losses.”

Campaigners called on the government to improve protections for suppliers and their workers who they said were at the “bottom of the pile” with no guaranteed payment from administrators.

In an open letter to ministers at the business department, Labour Behind the Label said the government had failed to “take a meaningful step forward in overseeing the poor behaviour and abusive purchasing practices of brands” following its report into the Leicester garment industry in 2020. It accused Missguided of a “reckless approach” towards managing its suppliers.

“UK law remains silent on the financial and legal responsibilities of companies to their supply chain workers. Suppliers, and supply chain workers are at the bottom of the pile as unsecured creditors in bankruptcy proceedings. This is deeply unfortunate,” the letter said.

Meanwhile, a number of former employees are considering legal action against the company over claims that the redundancy process was not properly managed.

One former employee said: “The entire company had a conference call with 25 minutes notice, people who weren’t there or on annual leave missed it. The call was an emotionless automated message saying that we had been made redundant and our services were no longer required.

“Many colleagues found out they had lost their jobs through social media, everyone is devastated.”

The company and its administrators declined to comment.

… as you’re joining us today from Japan, we have a small favour to ask. Tens of millions have placed their trust in the Guardian’s fearless journalism since we started publishing 200 years ago, turning to us in moments of crisis, uncertainty, solidarity and hope. More than 1.5 million supporters, from 180 countries, now power us financially – keeping us open to all, and fiercely independent.

Unlike many others, the Guardian has no shareholders and no billionaire owner. Just the determination and passion to deliver high-impact global reporting, always free from commercial or political influence. Reporting like this is vital for democracy, for fairness and to demand better from the powerful.

And we provide all this for free, for everyone to read. We do this because we believe in information equality. Greater numbers of people can keep track of the global events shaping our world, understand their impact on people and communities, and become inspired to take meaningful action. Millions can benefit from open access to quality, truthful news, regardless of their ability to pay for it.