Kenya election: How a handshake changed Odinga’s heartland

The road to his home in the small but busy town of Bondo – about 60km (37 miles) from the lakeside city of Kisumu – has been re-tarmacked, along with the road to the home of his late father, Mzee Jaramogi, as Kenya’s first post-independence vice-president is reverentially known to Kenyans.

Mzee Jaramogi served in the government of Jomo Kenyatta, the father of the current president, until they fell out, resulting in the vice-president becoming an opposition politician and being imprisoned in 1969 for 18 months.

It started a long period of enmity between the two families, which ended in 2018 with a now-famous handshake between Mr Odinga and Mr Kenyatta.

“The two roads were done after the handshake. We are hopeful that the tarmac will be extended into other villages if he [Mr Odinga] becomes president,” garage owner Isaac Omondi said, pointing out that Bondo has already received a “facelift” with potholes fixed and the drainage system improved.

Baba has really fought for democracy in this country. Because of him we’ve seen governments being kept in check”

The 77-year-old Mr Odinga’s home is heavily guarded by armed officers, as is the norm with every presidential candidate’s residence in the run-up to elections.

A peek inside shows a big mansion with an extended foyer complete with huge pillars.

At the far corner of his land stands the Lego Maria Church, an African-initiated offshoot of the Roman Catholic Church. Locals said Mzee Jaramogi belonged to it and his son donated the land for the church where neighbours come to worship.

The home of his father is open to the public and has been converted to a museum preserving the history of the Odingas, their Luo community, and Kenya as a whole.

IMAGE SOURCE,VIOLA KOSOME

IMAGE SOURCE,VIOLA KOSOMEIt includes personal items belonging to Mzee Jaramogi, such as his iconic hats, walking sticks, an empty bottle of his favourite premier wine, his pre-independence prison uniform and two gramophones.

At the far right near the museum’s main entrance, stands the first home that Mr Odinga constructed out of timber.

“Mr Odinga built it in a rush just before he went back to Germany [in the late 1960s] for his studies. His father set a condition that he needed to build a house and get married before returning to Germany,” said museum curator Mercellus Otieno.

At the museum hang the portraits of Kenya’s four presidents. Space has been left for the fifth one.

Many in Bondo hope that after the 9 August election, it will be filled with Mr Odinga’s portrait – not that of his main challenger, Deputy President William Ruto.

This is also the hope of Mr Kenyatta, who – after defeating Mr Odinga in two heavily disputed elections – is backing him as his successor.

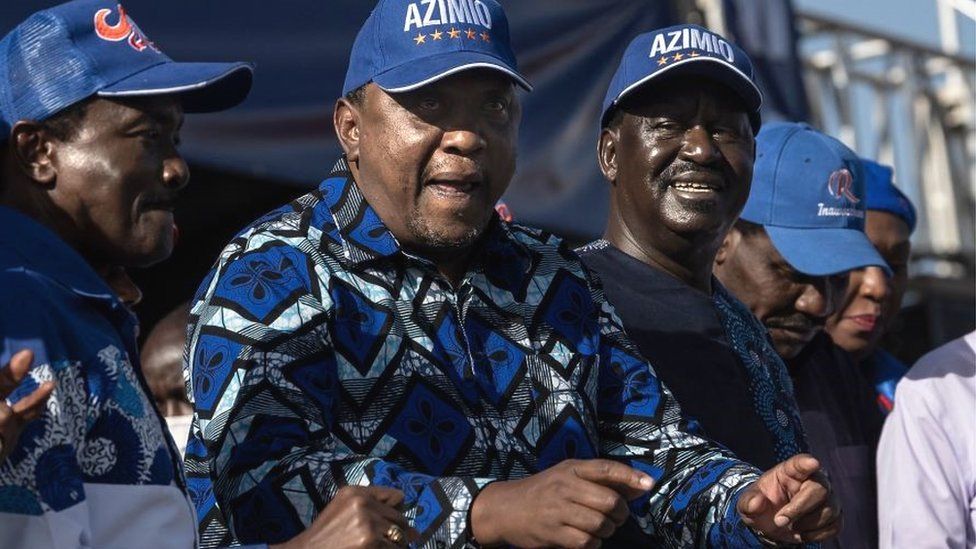

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESMr Odinga’s critics say he has gone soft in his criticism of corruption in the government since the handshake, while Mr Ruto has cast their pact as an attempt by two “dynasties” to stitch up power.

But as far as supporters of “Baba” – or Father, as Mr Odinga is affectionately referred to – are concerned, he deserves to lead Kenya as he has played a pivotal role in the campaign to end one-party rule, only to be robbed of victory – in their view – in four multi-party elections since then.

“Baba has really fought for democracy in this country. Because of him we’ve seen governments being kept in check. I am really proud of him and hopeful that he will be next president,” Mr Omondi said.

With the dire state of the economy and unemployment a huge issue for Kenyans, Mr Odinga’s manifesto is heavily anchored on manufacturing and industrialisation to create jobs.

He has also promised two million needy households a monthly stipend of 6,000 Kenyan shillings ($50; £40) from a new social protection fund if he is elected president.

But Mr Omondi, while fixing a faulty vehicle engine in his garage, said that most residents of Bondo do not want handouts.

“We don’t want free money. We want to work hard for our money. All we need him to do is to ensure the informal sector is supported because it employs many people,” the 46 year old added.

IMAGE SOURCE,VIOLA KOSOME

IMAGE SOURCE,VIOLA KOSOMEIn the last year the port and railway in Kisumu county have been revived along with a new network of roads across western Kenya – a development welcomed by lorry driver John Atwoto.

“The port has increased the demand for trucks here. Accessing [the towns of] Kakamega and Kitale is easier now and this has saved us a lot of time on the road,” he said.

The handshake has also eased tensions between Luos and Kikuyus, the ethnic group to which Mr Kenyatta belongs.

A Kikuyu restaurant owner, Benjamin Mwangi, said that unlike in the last two elections, when he feared violence, he would not leave Kisumu this time around.

Mr Odinga has increased his sense of security by choosing a Kikuyu – Martha Karua, who once served in the late Mwai Kibaki’s government as justice minister – as his running-mate.

“I do not foresee violence. We Kikuyus have Martha Karua as Odinga’s deputy so we are in his government [if he wins],” Mr Mwangi said.

In contrast some Kalenjins – the ethnic group to which Mr Ruto belongs – are leaving Kisumu.

Butcher Silas Lelei, 25, said his wife and child had already travelled to their home in Mr Ruto’s heartland of Eldoret.

He plans to close his business and join them shortly before the election, and will return only after results are announced and any disputes resolved.

“I can’t stay here. I don’t feel safe. I’ll close on 1 August until after elections,” he said while cutting a chunk of meat for a customer.

If Mr Odinga wins, it will be a moment of huge pride for his community as he will be the first Luo to become president.

For Lucas Obwar, a tyre repairer in Kisumu city, the victory would make it easier for Luos to get jobs in the public sector.

IMAGE SOURCE,VIOLA KOSOME

IMAGE SOURCE,VIOLA KOSOME“When we apply for jobs in national agencies, we don’t get them because we have never had a president to place our community high up,” Mr Obwar said.

Fishing is a major economic activity in Kisumu county and residents hope an Odinga presidency will finally make a fish-processing plant a reality.

“The processing industry will create jobs and increase revenue,” resident Nelson Adul said.

There is a joke in Kenya that fish costs more in Kisumu than elsewhere – and a dish of fried fish from women selling by the side of the lake was four times what would be expected.

Fishermen at Dunga beach, like Denis Morio, blamed middlemen for this and “decreasing our earnings”.

He said the facilities at a processing plant would make it easier to freeze their catch so they would have more time to negotiate better prices, with options to fillet the fish for export too.

Kisumu city also used to be home to a cotton milling factory, Kicomi, and a sugar factory, Miwani.

Both companies were run down by mismanagement. Thousands of people became jobless.

The poor neighbourhood of Obunga near the dilapidated Kicomi factory has houses made of iron-sheets and others are mud-walled.

This is where former factory workers-turned-hawkers live.

Isaiah Onyango, 58, remembers the times when the cotton factory had three work shifts.

“Rental houses were a booming business. Young people were getting jobs immediately after school,” he said, as he expressed the hope that Mr Odinga would rise to the presidency – and that Kisumu would then rise too after what he believes to be decades of neglect until the famous handshake.