Largest dam removal in US history approved

The federal government is giving the greenlight to the largest dam removal in U.S. history, paving the way for unprecedented restoration of the Klamath River basin in California and Oregon.

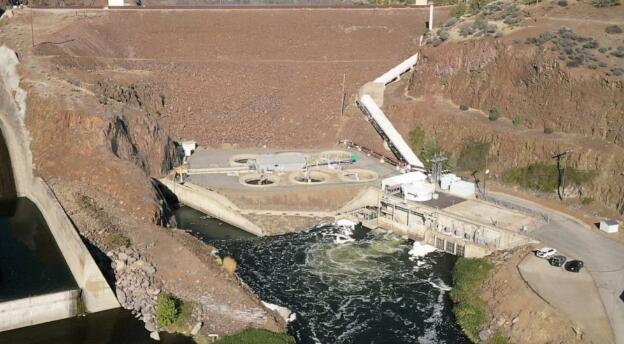

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has given the final stamp of approval for four dams along the lower Klamath River to be removed, reinstating access to more than 300 miles of habitat for salmon and improving water quality. After years of talks, FERC said on Thursday that they “approve the surrender of the Lower Klamath Project license and the proposed removal of the four project developments [the dams].”

This comes after a decades-long push from river basin tribes whose livelihood and culture are intertwined with the river. The Yurok Tribe told ABC News that if the salmon disappear from the river – so do they as a people.

“Salmon are a keystone species for their survival of this ecosystem that we’re a part of. And if there ever comes a time when there’s no more salmon in the river, then our ecosystem will have failed completely and won’t be able to sustain our life here on this world,” Frankie Myers, vice chair of the Yurok Tribe, told ABC News.

ABC News spent two days along the Klamath River – California’s second largest river – and its largest tributary, the Trinity, in which the Yurok Tribe has spent years conducting river restoration projects trying to bring back the salmon that have been there for thousands of years. With low levels and warming waters, and the dams blocking their passages to and from the ocean, some species of salmon are nearing extinction.

“The fish that are produced here, they have to transit the Klamath two times during their life. They have to transit it on their way out to the ocean in the summer, and then they have to come back in the summer and fall as adults. The conditions in the lower Klamath are a bottleneck… Last year we had a huge juvenile fish kill on the Klamath, where we lost 80-90% of migrating juveniles,” Kyle DeJulio, a biologist for the Yurok Tribe, told ABC News. “Taking the dams out and restoring the Klamath River is vital to the entire system.”

The Yurok Tribe depend on the salmon both spiritually, as well as a major part of their diet. Now, nearly 92% of basin tribal members face food insecurity, according to the University of California, Berkeley.

Molli Myers, Frankie Myers’ wife, told ABC News what their pantries look like when they don’t have an abundance of fish.

“They’ll be pretty bare,” Molli Myers said, as she showed what was left of the salmon they caught last year and canned. The tribe relies on salmon as a staple of their diet and say it’s unhealthy and unnatural when they have no choice but to supplement that diet.

Frankie and Molli Myers have spent their entire relationship fighting for dam removal over the past 20 years, since a fish kill in 2002 killed an estimated 34,000 fish in the Klamath River, a flashpoint that lead the tribes to call for the removal of the four lower Klamath dams.

Many of the people that will be on the front lines working to remove the dams over the next few years are tribal members themselves who have also been working on river restoration.

“I think it is really important that, you know, we take a look at, you know, what we have done as humans to damage these ecosystems. And, you know, take responsibility and let’s try to, you know, turn it around and do some good, you know,” Alderon McCovey told ABC News. McCovey is running the excavator, removing mine tailings from the Gold Mine rush for the largest restoration project to date along the Trinity.

When that project is done, it will have restored the floodplain habitat by 1,000%, according to the Yurok Tribe.

PacifiCorp, who owns and operates the dams, supports the removal saying it makes financial sense – costing an estimated $450 million to take them out, which they feel is a less expensive option than making environmental retrofits. PacifiCorp tells ABC News these dams provide no irrigation water, and very little hydropower as it is 2% of their portfolio, which they can replace with another clean energy.

The major opponents of the removal can be found in Siskiyou County, where leaders told us 80% of community members voted against the removal in 2010. County leaders say the reservoir behind the Copco dam is vital to firefighting efforts – allowing for easy aircraft water pickup.

Brandon Criss, assistant county supervisor for District 1 in Yreka, told ABC News that property values in the area are dropping with the impending removal – waterfront properties will be surrounded by land once the reservoir is emptied.

“I fear for the consequences when the dams come out. The flooding, the sediment … the loss of value to property, homes. And I’m worried that once the hoopla is done, this county will be left holding the bag for the consequences – the negative consequences of that. Everybody else wash their hands of it. It will have to live with it for generations,” Criss said.

Even supporters of dam removal admit that the removal alone might not revive the salmon population. The salmon have to spend time in the ocean, and with an increasingly unhealthy ocean environment, the fish still have to battle to survive.

Still, this is momentous, historic, and exciting for Frankie and Molli Myers and all the tribal members in the basin.

“I’m always going to try and represent who we are to the world,” Molli Myers said, who carries on customs like cooking acorns, basket weaving and proudly wears the traditional face tattoos of her ancestors

California Gov. Gavin Newsom called Thursday’s decision a culmination of “more than a decade of work to revitalize the Klamath River and its vital role in the tribal communities, cultures and livelihoods sustained by it.”

Oregon Gov. Kate Brown called this not just an ecological restoration, but “also an act of restorative justice,” going on to say “since time immemorial, the Indigenous peoples of the Klamath Basin have preserved the lands, waters, fish, and wildlife of this treasured region — and this project will not only improve its water and fish habitat, but also boost our economy.”

Work to shore up the roads surrounding the four dams will begin in early 2023, with the aim of actually removing the dams in early 2024.