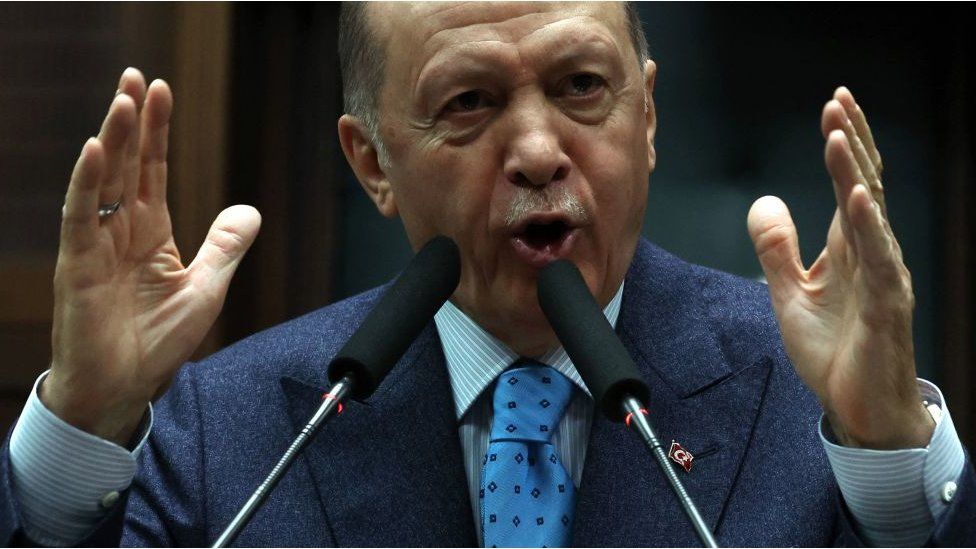

Turkey elections: Biggest test for Erdogan amid cost of living crisis

“I was paying 4,500 liras ($240; £195) for rent last year, but my landlord said he needed to raise the price,” said Seda. “We doubled the amount we pay, but he still asked us to leave the flat.”

She is one of millions of Turks struggling to cope with the cost of living in a country where the official inflation rate is higher than 57%.

Against this backdrop of economic turbulence, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has announced elections for 14 May in a bid to stay in power, after 20 years at the top.

Parliamentary and presidential elections will be held on the same day and polls suggest both will be very tight.

Seda’s search for a flat continues, but rents have surged as high as 30,000 liras – and her earnings have not kept pace: “I feel very vulnerable – as though I’m in a jungle, trying to survive.”

Hoping to stimulate the economy, President Erdogan has announced record public spending.

His plan includes energy subsidies, a doubling of the minimum wage and pension increases, as well as the chance for more than two million people to retire immediately.

But one elderly man shopping for groceries in a street market in Istanbul was unimpressed.

“We have become poorer all of a sudden this year. I think that the inflation we feel on the street is 600%, but the rise in pensions is only 30%,” he said.

Some analysts argue that an earlier election date could help President Erdogan capitalise on his stimulus measures.

But Global Source Partners Turkey consultant Atilla Yesilada believes that inflation will eat into the pay rises too soon.

“Unless there is another wage and pension adjustment… the feeling of gratitude that some voters currently feel will dissipate rapidly,” he said.

President Erdogan’s main opposition is an alliance of centre-left and right-wing parties, known as the Table of Six.

They have pledged to reverse his economic policies, introduce a tighter monetary policy and restore central bank independence.

But they are yet to pick a presidential candidate.

A decision is likely to come on 13 February and many expect they will choose Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the leader of Turkey’s main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP).

Another much-discussed figure is Istanbul’s mayor Ekrem Imamoglu.

Last month a court banned the mayor from politics for allegedly insulting electoral officials and sentenced him to nearly three years in prison – in a case he dismissed as politically motivated. He is still in office while he appeals against the judgement.

Soner Cagaptay from The Washington Institute think tank believes any attempt to ban the mayor of Istanbul from political life could backfire.

He points out that President Erdogan himself was in a very similar situation in the 1990s – a popular and successful mayor of Istanbul who was banned from politics by Turkey’s secular courts.

“That made him a martyr and a hero and he made a spectacular comeback,” said Mr Cagaptay.

It is Turkey’s third-biggest party that could play the role of kingmaker.

The Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) is pro-Kurdish. In January its state funding was cut off by Turkey’s top court and it could even be banned for alleged links to Kurdish militants.

Its former co-leader Selahattin Demirtas has been jailed since 2016, accused of “spreading terrorist propaganda”.

The party’s vice chair Hisyar Ozsoy admits that the authorities could shut them down. But he says it won’t stop his party, or the people who support it.

“Even if it is banned, our people will find ways to enter the elections by using some other political parties,” he said.

If the presidential race goes to a second round, the HDP’s support will most probably determine Turkey’s next president.

No-one yet has officially declared their candidacy for the presidency, including President Erdogan himself. There is a debate on whether he should even be allowed to run, since he has already been elected twice – the maximum limit.

Article 101 in the Turkish constitution states that “a person may be elected as president of the republic for two terms at most”.

“If Erdogan wants to run he will run,” said Mr Cagaptay.

“Because his brand is that he is the underdog fighting the elites, it might actually help his case if someone came up and said he’s not allowed. This is the kind of argument that has helped Erdogan in the past.”

There is a lot at stake in the upcoming elections, with opposition figures arguing that it will be a choice between increasing autocracy or democracy. The ruling AKP says only it can bring the cost of living down and sustain stability.

For Mr Erdogan, who has led Turkey since 2003, first as prime minister and later as directly elected president, the vote will decide whether his rule will go into a third decade.