What now for Wagner after Prigozhin’s reported death?

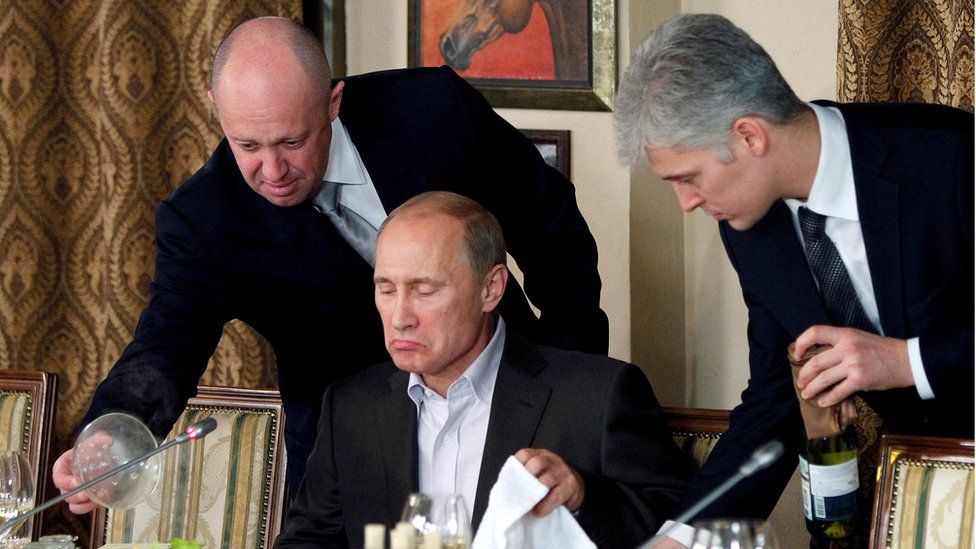

Yevgeny Prigozhin spent almost a decade building the Wagner paramilitary group.

It became central to Russia’s war effort in Ukraine and Prigozhin’s troops helped to spread Russian influence across the globe, propping up allies of President Vladimir Putin in Africa and Syria.

Now his death has sparked a flurry of speculation about the group’s future.

Western security officials are wondering who will take his place and what will happen to the mercenaries he once led.

Who will run Wagner now?

Dr Joana de Deus Pereira, senior research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (Rusi), told the BBC’s World Tonight programme that Prigozhin’s death would likely lead to “a certain revamping” of the group.

But she said that overall Wagner’s operations would probably continue in much the same way as it had under Prigozhin’s leadership.

“The organisation will persist in the future probably with another name, but it has already proved it has the capacity to adapt and to morph,” she said.

“We have to look at Wagner not only as a single man but as an ecosystem, as a hydra with many many heads and many diverse interests in Africa.”

Ruslan Trad, a security analyst with the Atlantic Council, agreed. He told the BBC that Prigozhin’s death would likely see someone with connections to Russia’s military intelligence service, the GRU, installed to lead the group in his place.

But he suggested that the main challenge for Mr Putin may be finding someone with deep enough pockets to fund the paramilitary’s operations, while not posing a direct challenge to his regime.

“They will try to find a new financier because Prigozhin was the main person with money there,” Mr Trad said.

“I think it will be more difficult to find a new financier because [Wagner] have good commanders, but money is important here. Maybe they will [install] someone from the close circle around Putin.”

Benoît Bringer, a journalist whose documentary The Rise of Wagner charted the paramilitary’s rise, told the BBC that one of the leading contenders is GRU General Andrey Averyanov.

“It is likely that Putin needed time to secretly organise the transition. This would explain why he waited two months before getting read of Prigozhin,” he added.

Emily Ferris of Rusi observed that Moscow “will have likely learned its lesson that personalities like Prigozhin with their own dangerous ambitions are a wildcard,” adding that “any new [Wagner] leader would likely be someone handpicked by the Kremlin”.

What will happen to Wagner’s troops in Belarus and Ukraine?

For much of the past year Wagner was Russia’s most effective fighting force in Ukraine, with its troops successfully taking the eastern cities of Soledar and Bakhmut after bloody battles.

But Ms Ferris said Prigozhin’s death was unlikely to seriously impact the course of the war.

“Wagner troops have been out of action in Ukraine since the rebellion, and their troops stationed either in Belarus, or absorbed back in to the Ministry of Defence, so the impact immediately on the Ukraine war, where the Russian forces are still holding back the Ukrainian counter-offensive, is likely to be minimal for now,” she observed.

She added that it appeared unlikely that Wagner troops would return to the battlefield in Ukraine, at least in the short term.

Meanwhile, around 8,000 Wagner troops are said to remain at camps in Belarus, having followed Prigozhin there after his failed uprising in June.

Their future is now unclear, with some reports on social media suggesting that several troops had made explicit threats against Mr Putin for what they alleged was his role in Prigozhin’s death.

Can Wagner troops in Africa and Syria keep fighting?

Equally unclear is the future of Wagner’s troops abroad. The group has become a key pillar of Russian foreign policy, with its forces helping to prop up governments in Syria, Mali, the Central African Republic and Libya in exchange for lucrative mining rights.

In recent days Prigozhin is believed to have been present in West Africa, where Western analysts fear the group was seeking to widen its reach into other countries, including Niger where a coup has just taken place.

Some had speculated that the decapitation of the group’s leadership could force Russia to re-evaluate its attempts to seek influence in the region, but many experts believe the group’s decentralised command on the continent should allow it to continue its operations unhindered by Prigozhin’s death.

Following June’s mutiny, Russian officials were reported to have flown to Libya to meet with Khalifa Haftar, the renegade general challenging the UN-recognised government in Tripoli, and assured him of the Wagner Group’s continued support, regardless of Prigozhin’s fate.

Mr Trad told the BBC that he believed Wagner was so heavily integrated in the defence infrastructure of African countries that their operations would be untroubled by Prigozhin’s death.

“The commanders stationed in Syria, or Central African Republic or Mali, they already have very good models in place there and they have the freedom to act,” he said.

“Local commanders are not impacted because the operations are separately operational, they have different resources for this and even now they are recruiting for Syria and Africa operations.”

And he said the group’s arms length relationship with Russian intelligence would remain a valuable tool for Moscow, allowing it to operate in the “grey zone” where it could pursue Russia’s interests, but allowing officials to deny involvement.

Mr Bringer told the BBC that Wagner’s was “essential in Africa” in terms of promoting Russian interests. “The structure will certainly continue to exist there, perhaps no longer under the name of Wagner, but with a new head loyal to the Kremlin,” he said.

Anton Mardasov, a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute’s Syria Program, said even in the wake of Prigozhin’s failed uprising in Russia, Wagner commanders abroad broadly avoided Kremlin reprisals to avoid “weakening Moscow’s overall position”.

But he said other mercenary companies were increasingly rivalling Wagner’s role in Syria. After June’s mutiny Mr Mardasov said that a number of Wagner troops had been offered a transfer to a competing company called PMC Redut.

“Redut has been working in Syria in parallel with Wagner for a long time,” Mr Mardasov told the BBC. “It is on the Redut that the military is betting in Syria, but they were afraid of fast steps.”

Will Wagner fade quickly from memory?

In the medium-term, therefore, it seems unlikely that Wagner’s operations will be significantly impacted by its benefactor’s death. But in the longer term Wagner’s operations look set reforming into something new, Emily Ferris of Rusi said.

“Most likely is that Wagner will splinter into two, with the remaining leaderless groupings in Belarus disbanded, and the other faction active abroad morphing into something else that can be a tool of Russian foreign policy,” she told the BBC.

As for Prigozhin’s legacy, Mr Bringer told the BBC that Wagner had “demonstrated to the Kremlin how a private shadowy army, capable of operating totally out of the law, could be useful in its hybrid wars, as well as to gain influence abroad.”

“The name of Wagner may disappear, but not the mercenaries in the field and the method he created.”